Snake River Mainstem

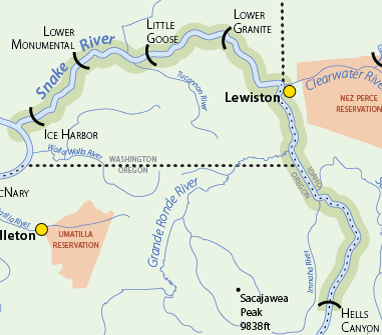

The original 1995 Snake River mainstem plan covered the stretch from Hells Canyon Dam to the river’s confluence with the Columbia River. The 2004 NPCC subbasin planning process separated this stretch into two plans: Lower Snake River Subbasin and Hells Canyon Subbasin.

Lower Snake River Subbasin

The Lower Snake Subbasin encompasses 1,059,935 acres (1,656 square miles) within portions Adams, Franklin, Walla Walla, Columbia, Whitman, Garfield and Asotin Counties in the southeastern corner of Washington State. This subbasin includes a portion of the Snake River Mainstem and a number of its tributaries, including Deadman Creek, Almota Creek, Alpowa Creek, and Penawawa Creek. Approximately 5 percent of the Snake River’s total watershed is located downstream of the Clearwater River at Lewiston, Idaho, and this region is relatively arid compared to the Snake River’s upstream drainage areas. As such, only a small portion of the Snake River mainstem flow is derived from tributaries located within the Lower Snake Subbasin. Vegetation in the subbasin is characterized primarily by grasslands and agricultural lands with some ponderosa pine, shrubsteppe, and wetland areas.

Hells Canyon Subbasin

The Snake Hells Canyon subbasin includes the mainstem of the Snake River and the small tributaries that flow into it as the Snake River flows from Hells Canyon Dam to the mouth of the Clearwater River at Lewiston, a length of 109 miles (river mile [RM] 247 to RM 138; Figure 1). The Snake River forms the border between Oregon and Idaho for the upper 71 miles of the subbasin and the border between Washington and Idaho for the lower 38 miles. The subbasin contains 862 square miles, or 551,792 acres. About 62% of this area falls in Idaho, 31% is in Oregon and the remaining 7% is in Washington. The subbasin contains part of five counties: Adams, Idaho, and Nez Perce in Idaho; Asotin in Washington; and Wallowa in Oregon. The lower portion of the subbasin contains the town of Asotin and portions of Clarkston and Lewiston. The remainder of the subbasin is either rural or undeveloped. The Salmon, Imnaha, Grande Ronde, and Clearwater rivers, as well as Asotin Creek, are major tributaries that join the Snake River in the Snake Hells Canyon subbasin. These rivers drain a combined area of 19,280 square miles (12,339,200 acres) and dramatically influence the water quality and hydrologic conditions in the Snake River.

Archaeological evidence suggests that the Snake Hells Canyon subbasin has been inhabited by Native Americans for the last 7,100 to 10,000 years. The subbasin’s relatively mild winters, lush forage, and plentiful wildlife made it a particularly attractive home. It was consistently inhabited by the Nez Perce and frequently visited by the Shoshone-Bannock, Northern Paiute, and Cayuse Indians. The canyon’s rock walls were an ideal canvas for ancient pictographs, and the inaccessibility of the subbasin has aided in their preservation. The unique geology and inaccessibility of the subbasin have made it a place of extreme cultural significance (USFS 1999). The entire subbasin is within the lands ceded by the Nez Perce Tribe to the federal government under the Treaty of 1855, and the tribe maintains treaty rights to fish, roots and berries, hunting, and pasture for horses and livestock in this area.

Ecosystem

The Snake Hells Canyon subbasin has a variety of characteristics that make it unique in the Blue Mountain Ecoprovince, most related to its being a mainstem subbasin. The Snake Hells Canyon subbasin is the only mainstem subbasin within the Blue Mountain Ecoprovince, and it consists primarily of a single large river and surrounding face drainages rather than a “classic watershed” where tributaries combine to form a mainstem prior to emptying into an even larger water body. Rather than being defined by headwaters and ridgetops, the upstream boundary of the Snake Hells Canyon subbasin is Hells Canyon Dam.

The prevalence of large mainstem river habitats within the Snake Hells Canyon subbasin in particular results in aquatic resources that are relatively unique within the Blue Mountain Ecoprovince. Although other areas within the ecoprovince are used by fall chinook salmon and white sturgeon, the mainstem habitats within the Snake Hells Canyon subbasin are disproportionately important to these two fishes. The mainstem Snake River below its confluence with the Salmon River also provides a critical component of the migration corridor for endangered Snake River sockeye salmon migrating back to Redfish Lake in Idaho. The mainstem Snake River also provides migration and rearing habitat for steelhead, spring chinook, and bull trout.

The mainstem nature of the subbasin makes a variety of management situations within this subbasin unique within the Blue Mountain Ecoprovince. Mainstem subbasins do not operate as independent units: a decision in one subbasin, such as the Lower Middle Snake subbasin, could have significant impacts on other mainstem subbasins both upstream and down. This relationship complicates the ability to address “out-of-subbasin effects,” which differ for upstream and downstream directions. (Upstream examples include water use and reduced sediment transport through reservoir systems. Downstream examples include mainstem transportation and passage, flow, harvest, ocean conditions, and the systemwide effects of artificial production.) These out- of-subbasin effects are often major drivers in biological performance or habitat conditions within mainstem subbasins, and, because of their magnitude and complexity, are difficult to define and characterize from a subbasin perspective.

Subbasin plans are stored on the Northwest Power and Conservation Council’s website. All links will open on their website.

Subbasin plans are stored on the Northwest Power and Conservation Council’s website. All links will open on their website.