Wy-Kan-Ush-Mi Wa-Kish-Wit 2014 Update

This is an update of the 1995 Wy-Kan-Ush-Mi Wa-Kish-Wit (the Spirit of the Salmon): The Columbia River Anadromous Fish Restoration Plan of the NEZ PERCE, UMATILLA, WARM SPRINGS and YAKAMA tribes. It supplements the 1995 Plan, using an adaptive management framework to describe progress and needed modifications to the original 1995 recommendations. It also identifies and addresses new challenges with new science and policy.

The 1995 Spirit of the Salmon Plan and the 2014 Update cover the basin’s upriver salmon species, Pacific lamprey, and white sturgeon. Salmon and lamprey are anadromous fish species—fish that migrate as juveniles from freshwater to saltwater and return to freshwater as adults to spawn. Since the massive dams were built on the Columbia River, white sturgeon populations above Bonneville Dam have been landlocked and managed as resident fish. For more about Columbia River salmon, lamprey, and white sturgeon, see Biological Perspective in the 1995 Spirit of the Salmon Plan.

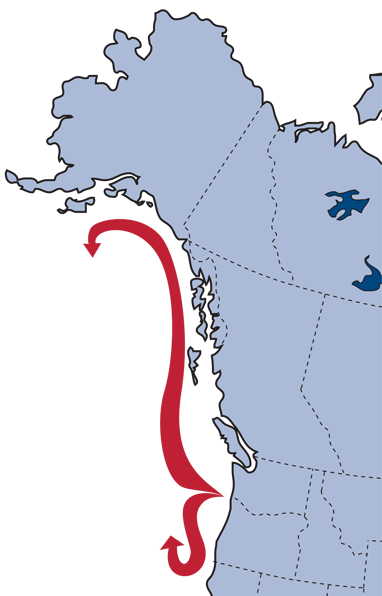

The geographic scope of the Plan corresponds to the migratory range of the upriver anadromous fish covered in this Plan. That range includes the Columbia Basin above Bonneville Dam, the entire mainstem of the Columbia River, and the Pacific Ocean as far north as Southeast Alaska and along Oregon’s northern coast.

In this Update, the Need for a Plan (below) recaps the reasons the tribes developed their own fish restoration plan. The goals and objectives are restated in the Spirit of the Salmon Goals and Objectives.

Spirit of the Salmon Basic Principles articulates how traditional values have blended with science to guide our restoration efforts. The Tribes’ Treaty Reserved Fishing Rights and Sovereignty and Consultation summarize the legal principles that guide the Plan and this Update. Sovereignty and Consultation provides background on tribal sovereignty and government-to-government relations and describes new developments since 1995. Traditional Ecological Knowledge, emerging terminology in 1995, elaborates on this basic principle.

Progress toward the protection and restoration of salmon, lamprey and sturgeon since release of the 1995 Spirit of the Salmon Plan is depicted in Summary of Accomplishments, We Have Halted the Salmon’s Decline and The Accords, Pacific Salmon Treaty, and U.S. v. Oregon Agreements. The Plan’s updated institutional and technical recommendations also discuss accomplishments.

The condition of anadromous fisheries a decade and a half after the Spirit of the Salmon Plan was published and how these populations are now trending is shown in a series of figures in Abundance Trends. Remaining Problems and Gaps and New Challenges and Opportunities summarize what else needs to be accomplished.

The outstanding actions are discussed further in updates of the 1995 Plan’s original 11 Institutional Recommendations and 13 Technical Recommendations. In these sections, the Update examines each of the 1995 institutional and technical recommendations, reporting on the problem or issue as it currently stands; assessing the results of actions taken; identifying remaining problems and gaps; and proposing modified and new actions.

The new challenges, those not identified in the 1995 Spirit of the Salmon Plan, are the basis for New Institutional Recommendations, New Technical Recommendations and New Community Recommendations. Issues and opportunities are summarized; actions to resolve or manage the issues are proposed; and desired outcomes identified.

For the new technical recommendations, an initial hypothesis about the problem and the needed solutions are presented and the anticipated results of the proposed actions are stated. This is an abbreviated version of the hypothesis/solution structure employed in the original 1995 Wy-Kan-Ush-Mi Wa-Kish-Wit technical recommendations. Note: The technical recommendations are presented in order of the salmon lifecycle (scroll to Table 5B.1 in 1995 Wy-Kan-Ush-Mi Wa-Kish-Wit, Technical Recommendations).

When we published the original Wy-Kan-Ush-Mi Wa-Kish-Wit, or Spirit of the Salmon Plan, in the last decade of the 20th century, we found ourselves in a dire situation in which our First Foods, our salmon, and our Big River were threatened and, in some places, gone.

Nearly unceasing and uncompromising industrial development typified by construction of large Columbia and Snake river hydroelectric and flood storage dams, large-scale floodplain development and alterations, and severely exploitative commercial fisheries, damaged the rivers’ ecological integrity and caused the crash of what were since time immemorial some of the world’s most productive salmon runs.

During this period of exploitation, many assumed that technology would fix the problems—dams with fish ladders, barges for moving juvenile salmon around the dams, industrial-style hatcheries, are a few examples. As the tribes witnessed, technology alone did not prevent the crash of Columbia Basin fish populations. Recognizing this, the tribes built their Spirit of the Salmon Plan on the natural structure and functions of the multiple ecosystems where salmon, lamprey, and sturgeon live combined with the wise use of technology.

The tribes also examined the human structures charged with the management and protection of the basin’s anadromous fisheries. What we saw in 1995 were five major institutions governing anadromous fish restoration. These institutions, as detailed in the Legal and Institutional Context of the Spirit of the Salmon Plan, were unable or unwilling to rebuild fish populations, particularly the upriver runs above Bonneville Dam that the tribes depend on. The U.S. v. Oregon Columbia River Fish Management Plan, the U.S.-Canada Pacific Salmon Treaty, the Columbia River Basin Fish and Wildlife Program, and the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission were, for various reasons, limited in scope or authority. The Endangered Species Act (ESA), on the other hand, provided the legal means to conduct comprehensive recovery of the basin’s salmon runs; yet, under the leadership of the National Marine Fisheries Service, the ESA had not fulfilled this promise.

In 1995 the biological circumstances of Columbia Basin salmon, lamprey and sturgeon populations were extreme: the fish continued to decline, moving ever closer to extinction. Dams blocked more than half of the historical anadromous fish habitat. Other water and land uses had also eliminated habitat, including critical floodplain and estuarine habitats. Elevated water temperatures, increased sediments, and toxic pollutants degraded the river system’s water—the “air that salmon must breathe.”

The operation of Columbia River dams and storage reservoirs had profound ecological impacts. Among them, the dramatic losses of juvenile salmon, estimated as high as 96% cumulative mortality through the nine-dam mainstem system (NMFS 1995). The adjacent figure shows the major dams of the Columbia and Snake rivers (in the United States). Numerous alternatives to juvenile salmon migrating through these hydropower dams and their generating turbines were but tried with very limited success. For adult migrating salmon, fish ladder design caused “fall back” over dam spillways and through turbines. Pacific lamprey fell victim to passage problems at the dams. White sturgeon were trapped between the dams and virtually unable to migrate through or around these structures.

Hatcheries, used in the Columbia River Basin primarily to compensate for losses caused by water development projects, were operated without regard for sustaining the historical geographic distribution of salmon. Most of this hatchery mitigation was not taking place where the damage had occurred. The mitigation supplied hatchery-produced fish to support lower river fisheries in lieu of helping to restore the natural populations in the upstream tributaries. Yet prior to non-Indian settlement, salmon persisted throughout the basin.

The Spirit of the Salmon Plan responded to the environmental and institutional crisis described above, proposing a series of hypotheses, referred to as technical recommendations, designed to lessen human-caused mortality of the species in question and a series of related institutional recommendations to manage the implementation of these hypotheses.

This Update examines where the Plan has taken us—the accomplishments, the remaining problems, and what lies ahead.