A Tribal Tradition of Sound Fish Management

The native peoples of the Columbia River Basin have always revered the way the Creator took special care of nature and the way nature obeyed the Creator. This was a perfect mystery. For that reason, Columbia River tribes found it easy to embrace the concept of stewardship. For them, stewardship extends respect for life beyond the dignity of the human person to the whole of creation. That respect involves the responsibility to honor what the Creator provides. As long as nature is taken care of, nature will take care of the people. The tribes continue to acknowledge this traditional wisdom.

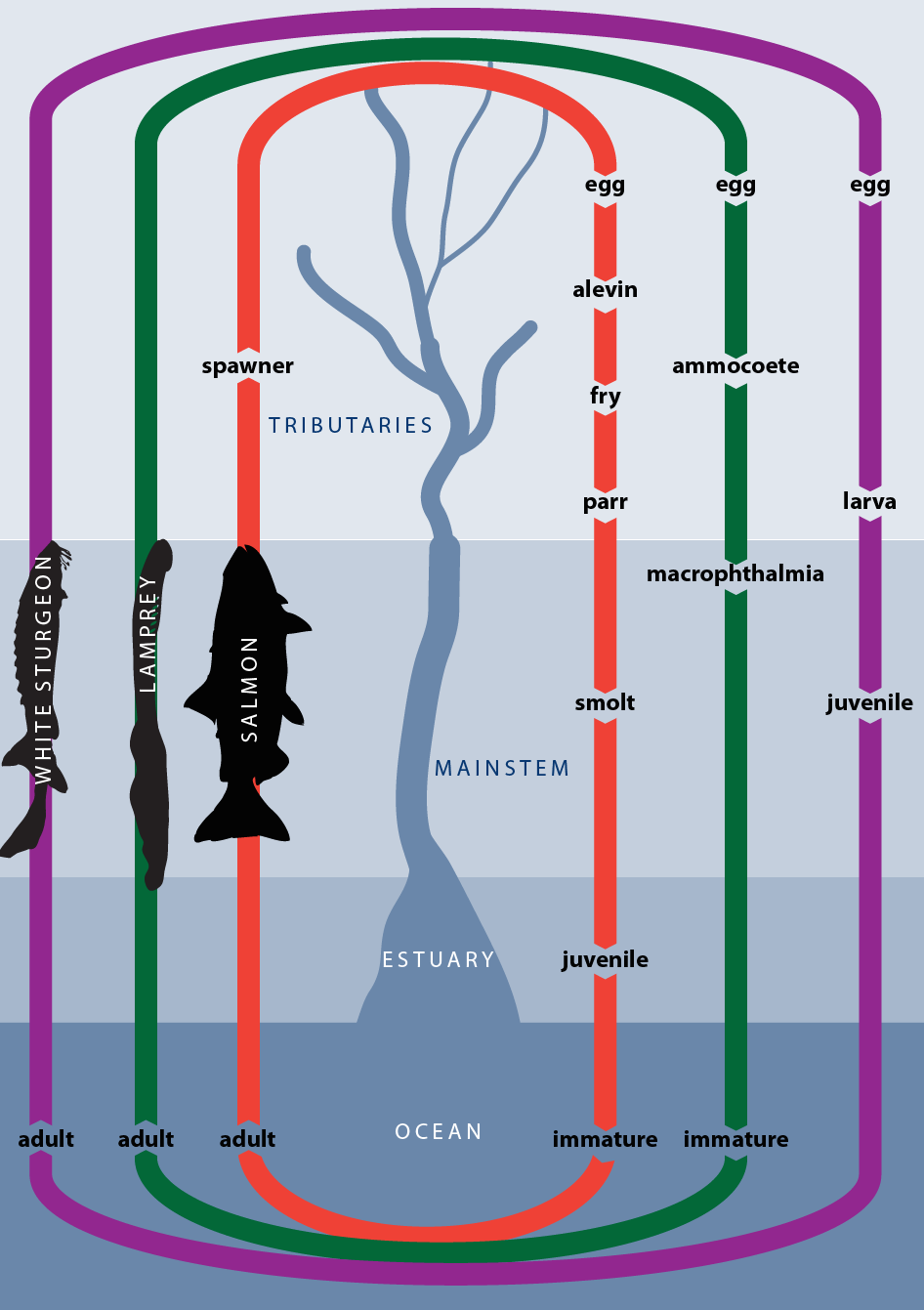

The tribes developed “gravel-to-gravel” management principles from this traditional wisdom. Gravel-to-gravel management acknowledges the relationship between the biology of the fish, the degree of human pressures on them, and the condition of their physical environment throughout all life history stages. It is an ecologically sound approach that is at the same time sacred and regulatory.

In non-Indian parlance, traditional wisdom is systems thinking. It is a discipline for seeing wholes, recognizing patterns and interrelationships, and learning how to structure human actions accordingly.

This way of thinking is the foundation of the recommendations for salmon restoration. The recommendations are intended to harmonize what Indian people know about the basin’s natural environment, what humans have imposed on that environment, and what can be done to create a balanced and sustainable existence.

Tribal management begins with a recognition of nature’s bounty as a gift from the Creator. They are humbled by the salmon’s faithful return to the rivers to serve human and other needs. Tribal people celebrate nature’s preeminence and the need for human society to harmonize itself with the structures and rhythms of nature. They believe that everything in nature has a purpose, whether or not humans know the purpose. Today tribal respect for nature is evidenced in time-honored ceremonies such as the seasonal first-food feasts held each year, when the human world stops to honor the return of nature’s gifts.

In the native cultures of the Columbia Basin, food and water were never taken for granted, as they often are in today’s society. Tribal society recognized that food and water are always matters of survival and of spiritual well-being.

Today people are often far removed from the sources of their food and drinking water. Very few are engaged in growing or gathering food for the table, and a growing number are no longer even involved in food preparation at home. Under such circumstances, it becomes difficult to appreciate our place in the natural cycles of life. Contemporary society is removed from what traditional native thinkers of the Columbia Basin called the “connectedness” or “connection of all life.”

Indian culture and religion are attentive to the human place within nature. A drink of water, the aroma of roasting salmon, or a bite of the crispy kouse (root) are ordinary reminders that all humans are dependents of nature. As we are served, we must also serve.

The complexity of human minds was simplified in the indescribable beauty of songs that expressed a culture based on the fundamentals of love, purity, respect, and worship which sustained life for natives before the time of Christianity, Judaism, or any other of the great world religions. This strength should not be lost.

Many laws and rules were the subject of the hundred or more songs that the people knew. In them were instructions on how to live, expressed in “a way that opens your mind up.” Some explained that as “the givers of life,” the salmon, the deer, the roots, and the berries must be enjoyed as food and in ceremony. How water and the four great foods are to be honored and cared for are also prescribed in the songs.

Non-Indian attempts to subjugate nature and the resulting spiritual bankruptcy are what many Indian people and others believe are among the root causes for many current environmental and social problems, including the salmon crisis.

Perhaps nowhere are the differences in the Indian and non-Indian ways of relating to nature more evident than in the treatment of water. The tribes have always regarded water as a medicine because it nourishes all of life. Water flushes poisons out of humans, other living creatures, and the land. Traditional culture teaches that to be productive, water must be kept pure. When water is kept pure and cold, it takes care of the salmon. It takes care of humans as well. Water that cannot take care of salmon cannot take care of humans.

Non-Indians, on the other hand, have used the water without fully understanding that it must be treated with respect to remain powerful. By causing the water to warm, by restricting its flow and by putting pollutants in it, they have made the water sick. It can no longer be used as a cleansing agent. The water is so inhospitable that at times it can no longer take care of the salmon.

After European-introduced diseases took their toll, after treaties and the reservation system were firmly installed, and as non-Indian cultural domination spread, a great deal of tribal “encyclopedic” knowledge of the natural and spiritual world was lost. What is known comes from tribal elders, from the study of the language and culture, from records, and from other analytical sources.

What is known, for example, is that hundreds and hundreds of plants, animals, and geographic locations were identified. Each of these plant and animal species had a particular purpose or use. Tribal people knew their characteristics and properties, the habitat and environmental conditions in which they could be found, and the ritual and practical methods for using and preserving them. For animals, tribal people also understood migration, nesting, and mating habits. For plants, they knew when, where, and which varieties could be picked.

Different types of biogeographic formations (of water and land) were distinguished. Plants, animals, and especially places were also repositories for historical, social, and spiritual lessons. This knowledge and more was transmitted to succeeding generations as part of their inheritance.

With regard to fish, each species was known by its shape, size, color, taste, and swimming and jumping abilities. Tribal people differentiated between anadromous and non-anadromous fish. In their taxonomy, steelhead are considered one of the salmon (nusux) by virtue of their anadromous habits, their size, and other characteristics.

Traditional tribal experts could distinguish among stocks of salmon. That is, they could tell for which tributary a run of salmon was destined. Tribal experts could predict the arrival of salmon by observing, for example, the new growth of grasses and shrubs.

Within the context of their systems frame of reference (i.e., their ecological and spiritual values), tribal people applied this extensive knowledge to fisheries practices and management. Today, tribal people use some of the same methods that were used for thousands of years. Rules and regulations, management areas, law enforcement, and research and analysis (the accumulated observations and interpretations described above) were all integral parts of tribal resource management. The result was that for thousands of years, and until the arrival of non-Indians, tribal leaders managed their resources successfully. The people fished, and the salmon returned.

The mainstem Columbia River was divided into territories, each with its own regulatory body. For example, on either side of the Celilo Falls fishing area were important territories. Downstream were Big Eddy and the Great Cascades, and upstream, a fishery was centered around what was later called John Day Falls. Among the tribes and bands who fished the river there was general recognition of each other’s areas, who fished there, and when. Although fishing rules varied according to area, they were similar and were usually enforced by a headman (sometimes referred to as a salmon chief) and his committee.

More is known about the Celilo Falls fishery because it was in continuous use until 1957. It was the last major fishing area in the Basin to be inundated by backwaters from dam construction. At Celilo, the headman was responsible for conducting an orderly fishery in compliance with the traditional laws of his people so that the salmon returned year after year.

Following the traditional law, the headman determined when and how long fishing occurred. For example, no fishing could take place until the first salmon feast was held. The headman determined when the feast would occur. To prevent over-harvest, fish were caught at their prime. A fisherman was to catch only what was needed for food or for trade. Wasting fish or parts of fish was prohibited. Even the head and backbone were used; they were, for example, made into a soup. Night fishing was prohibited to allow upstream-destined salmon to continue to spawning grounds.

To maintain an orderly fishery, a headman, along with his committee, enforced other regulations. They often dealt with matters such as property rights, standards of behavior, polluting the water, or safety. Fishing sites were individually owned and were inherited. Owning a site did not mean that only one family would benefit. Unwritten but understood ethics of sharing dictated an owner allow another the opportunity to catch at least one fish or might require that preference be given to elders. However, a nonowner always sought permission to use another’s site. For rule breakers, there were punishments, often involving banishment from the fishing area for a day, a fishing season, or in extreme causes, longer.

It is important to note that tribal people did not rely exclusively on salmon. Such a reliance would not have been very practical. Fishing was mostly an intermittent spring-to-early-fall activity. Most places were fished only during certain times of the year.

Rather than being permanently located in fishing villages, most of the people of the Columbia Basin made the seasonal round. At each place, they carefully appropriated nature’s abundance and moved on. Seasonal movement avoided overuse of resources and abuse of the environments that supported them. A typical seasonal round took village members from their winter lodges near the rivers, to root-digging fields, to fishing areas, to the mountains for summer recreation and berry picking, to the big river for fishing and other activities, and back again to the winter lodge.

During winter, village leaders made what we now call resource management plans. Based on accumulated knowledge and current observations such as weather, water conditions, animal behavior, and other data, they planned for the next year’s seasonal round. Evolving over thousands of years, the seasonal round—with significant dependence on fisheries—was a successfully managed, sustainable lifestyle compatible with the basin’s environment.