Wind River Subbasin Plan

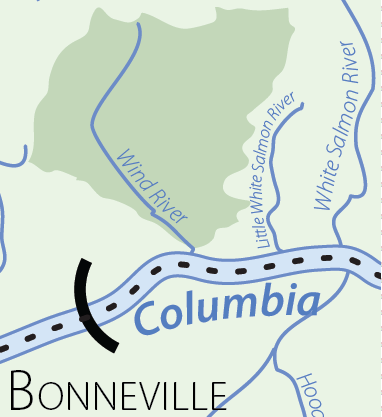

The Wind River is one of eleven major subbasins in the Washington portion of the Lower Columbia Region. This subbasin historically supported abundant fall Chinook, winter steelhead, chum, and coho. Today, numbers of naturally spawning salmon and steelhead have plummeted to levels far below historical numbers. Chinook, steelhead and chum have been listed as Threatened under the Endangered Species Act and coho is proposed for listing. The decline has occurred over decades and the reasons are many. Freshwater and estuary habitat quality has been reduced by agricultural and forestry practices. Key habitats have been isolated or eliminated through Bonneville Pool inundation, channel modifications, and floodplain disconnection. Altered habitat conditions have increased predation. Competition and interbreeding with domesticated or non-local hatchery fish has reduced productivity. Hydropower construction and operation has altered flows, habitat, and migration conditions. Fish are harvested in fresh and saltwater fisheries.

Wind River coho salmon and summer steelhead will need to be restored to a high level of viability to meet regional recovery objectives. This means that the populations are productive, abundant, exhibit multiple life history strategies, and utilize significant portions of the subbasin.

In recent years, agencies, local governments, and other entities have actively addressed the various threats to salmon and steelhead, but much remains to be done. One thing is clear: no single threat is responsible for the decline in these populations. All threats and limiting factors must be reduced if recovery is to be achieved. An effective recovery plan must also reflect a realistic balance within physical, technical, social, cultural and economic constraints. The decisions that govern how this balance is attained will shape the region’s future in terms of watershed health, economic vitality, and quality of life.

This plan represents the current best estimation of necessary actions for recovery and mitigation based on thorough research and analysis of the various threats and limiting factors that impact Wind River fish populations. Specific strategies, measures, actions and priorities have been developed to address these threats and limiting factors. The specified strategies identify the best long term and short term avenues for achieving fish restoration and mitigation goals. While it is understood that data, models, and theories have their limitations and growing knowledge will certainly spawn new strategies, the Board is confident that by implementation of the recommended actions in this plan, the population goals in the Wind River Basin can be achieved. Success will depend on implementation of these strategies at the program and project level. It remains uncertain what level of effort will need to be invested in each area of impact to ensure the desired result. The answer to the question of precisely how much is enough is currently beyond our understanding of the species and ecosystems and can only be answered through ongoing monitoring and adaptive management against the backdrop of what is socially possible.

Key Priorities

Many actions, programs, and projects will make necessary contributions to recovery and mitigation in the Wind River Subbasin. The following list identifies the most immediate priorities.

1. Reduce Passage Mortality at Bonneville Dam and Mitigate for Effects of Reservoir Inundation

Anadromous fish populations in the Wind River are affected by Bonneville Dam operations including inundation of historically available key habitat in the lower river and dam passage effects. Almost a mile of spawning habitat was inundated by Bonneville Pool. This loss of key habitat is particularly significant due to the naturally limited amount of suitable habitat in the lower basin for fall Chinook, chum, and coho. Upstream and downstream fish passage facilities are operated at Bonneville Dam in the mainstem Columbia River but significant mortality and migration delay occurs. Adults are typically delayed in the tailrace but most eventually find and use fish ladders. A varying percentage of adults do not pass successfully or pass but fall back over the spillway. Juvenile passage mortality results primarily from passage through dam turbines rather than spillway or fish bypass systems. Anadromous fish populations will benefit from regional recovery measures and actions identified for operations of Bonneville Dam with respect to fish passage. The suite of in-subbasin and out-of-subbasin actions will help to mitigate for habitat loss and dam passage impacts.

2. Protect Intact Forests in Headwater Basins

Portions of the Wind Subbasin, particularly those protected through Wilderness and Late Successional Reserve designations, are heavily forested with relatively intact landscape conditions that support functioning watershed processes. Streams are unaltered, road densities are low, and riparian areas and uplands are characterized by mature forests. Existing legal designations and management policy are expected to continue to offer protection to these lands.

3. Manage Forest Lands to Protect and Restore Watershed Processes

The majority of the Wind Subbasin has been managed for commercial timber production and has experienced intensive past forest practices activities. Proper forest management is critical to fish recovery. Past forest practices have reduced fish habitat quantity and quality by altering stream flow, increasing fine sediment, and degrading riparian zones. In addition, forest road culverts have blocked fish passage in small tributary streams. Effective implementation of new forest practices through the Department of Natural Resources’ Habitat Conservation Plan (state lands), Forest Practices Rules (private lands), and the Northwest Forest Plan (federal lands) are expected to substantially improve conditions by restoring passage, protecting riparian conditions, reducing fine sediment inputs, lowering water temperatures, improving flows, and restoring habitat diversity. Improvements will benefit all species, particularly summer steelhead.

4. Manage Growth and Development to Protect Watershed Processes and Habitat Conditions

The human population in the basin is relatively low, but it is projected to grow by 50% in the next twenty years. The local economy is also in transition with reduced reliance on forest products. Population growth will primarily occur in the lower basin in and around Carson, WA and along the lower and middle mainstem Wind River in privately owned areas. This growth will result in the conversion of forest land to residential uses, with potential impacts to habitat conditions. Land-use changes will provide a variety of risks to terrestrial and aquatic habitats. Careful land-use planning will be necessary to protect and restore natural fish populations and habitats and will also present opportunities to preserve the rural character and local economic base of the basin. The assessments illustrate the overwhelming importance of the Wind River canyon and Panther Creek canyon reaches for summer steelhead juvenile rearing. These reaches have been relatively protected from riparian impacts due to the steepness of the canyons and lack of near-stream roadways. Effective recovery of steelhead will require that no further degradation of these important reaches occurs. An additional concern is development adjacent to the lower mainstem Wind that has altered natural runoff processes, resulting in severe erosion and sedimentation of stream channels. These processes are exacerbated by highly erodable soils. Implementing stormwater runoff controls and working to restore existing runoff and erosion problems will benefit fish habitat in lower river reaches. Targeting conditions along the lower river could provide important benefits to winter steelhead and fall Chinook, which typically do not ascend Shipherd Falls at river mile 2.

5. Restore Floodplain Function, Riparian Function and Stream Habitat Diversity

The middle mainstem Wind upstream of the Trout Creek confluence and extending into National Forest Land consists of a broad alluvial floodplain valley that has been impacted by land-use activities including past agricultural practices, residential development and associated channel modifications. Construction of levees, bank stabilization, and riparian vegetation removal have heavily impacted fish habitat in these areas. Removing or modifying channel control and containment structures to reconnect the stream and its floodplain, where this is feasible and can be done without increasing risks of substantial flood damage, will restore normal habitat-forming processes to reestablish habitat complexity, off-channel habitats, and conditions favorable to steelhead spawning and rearing. Partially restoring normal floodplain functions will also help control downstream flooding and provide wetland and riparian habitats critical to other fish, wildlife, and plant species. Existing floodplain function and riparian areas will be protected through local land use ordinances and partnerships with landowners. Restoration will be achieved by working with willing landowners, non-governmental organizations, conservation districts, and state and federal agencies.

6. Evaluate and Address Passage Issues at Hemlock Dam and Lake and Other Barriers

Hemlock Dam and Lake on Trout Creek are believed to create passage issues for adult and juvenile steelhead. Dam removal is currently being evaluated as a means to improve passage conditions and allow for the restoration of aquatic habitat at the existing dam and lake site. Other passage barriers in the basin are located on small tributaries and are not believed to block a significant portion of habitat. Passage restoration projects should focus only on cases where it can be demonstrated that there is good potential benefit. Further assessment and prioritization of passage barriers is needed throughout the basin.

7. Align Hatchery Priorities with Conservation Objectives

Hatcheries throughout the Columbia basin historically focused on producing fish for fisheries as mitigation for hydropower development and widespread habitat degradation. Emphasis of hatchery production without regard for natural populations can pose risks to natural population viability. Hatchery priorities must be aligned to conserve natural populations, enhance natural fish recovery, and avoid impeding progress toward recovery while continuing to provide fishing benefits. Hatchery programs in the Wind Basin will produce and/or acclimate spring Chinook for use in the subbasin. Spring Chinook hatchery programs continue to support harvest as part of Columbia Basin Hydrosystem mitigation.

8. Manage Fishery Impacts so they do not Impede Progress Toward Recovery

This near-term strategy involves limiting fishery impacts on natural populations to ameliorate extinction risks until a combination of measures can restore fishable natural populations. There is no directed Columbia River or tributary harvest of ESA-listed Wind River salmon and steelhead. This practice will continue until the populations are sufficiently recovered to withstand such pressure and remain self-sustaining. Some Wind River salmon and steelhead are incidentally taken in mainstem Columbia River and ocean mixed stock fisheries for strong wild and hatchery runs of fall Chinook and coho. These fisheries will be managed with strict limits to ensure this incidental take does not threaten the recovery of wild populations including those from the Wind. Steelhead and chum will continue to be protected from significant fishery impacts in the Columbia River and are not subject to ocean fisheries. Selective fisheries for marked hatchery steelhead and coho (and fall Chinook after mass marking occurs) will be a critical tool for limiting wild fish impacts. State and federal legislative bodies will be encouraged to develop funding necessary to implement mass-marking of Fall Chinook, thus enabling a selective fishery with lower impacts on wild fish. State and federal fisheries managers will better incorporate Lower Columbia indicator populations into fisheries impact models.

9. Reduce Out-of-Subbasin Impacts so that the Benefits of In-Basin Actions can be Realized

Wind River salmon and steelhead are exposed to a variety of human and natural threats in migrations outside of the subbasin. Out-of-subbasin impacts include drastic habitat changes in the Columbia River estuary, effects of Columbia Basin hydropower operation on mainstem, estuary, and nearshore ocean conditions, interactions with introduced animal and plant species, and altered natural predation patterns by northern pikeminnow, birds, seals, and sea lions. A variety of restoration and management actions are needed to reduce out-of-subbasin effects so that the benefits of in-subbasin actions can be realized. To ensure equivalent sharing of the recovery and mitigation burden, impacts in each area of effect (habitat, hydropower, etc.) should be reduced in proportion to their significance to species of interest.

Subbasin plans are stored on the Northwest Power and Conservation Council’s website. All links will open on their website.

Subbasin plans are stored on the Northwest Power and Conservation Council’s website. All links will open on their website.