Regional and International Salmon Agreements

Three 2008 agreements expanded efforts to address numerous institutional and technical problems identified in the 1995 Spirit of the Salmon Plan. These landmark agreements made improvements in the fragmented and process-laden management of Columbia River Basin salmon. The agreements helped to streamline and coordinate decision-making and in ways that encourage cooperation among the tribes and federal and state governments. Together the three—the Columbia Basin Fish Accords, the Pacific Salmon Treaty, and the U.S. v. Oregon Agreements—provide an institutional framework for implementing the Spirit of the Salmon Plan during most of the remainder of its planned duration.

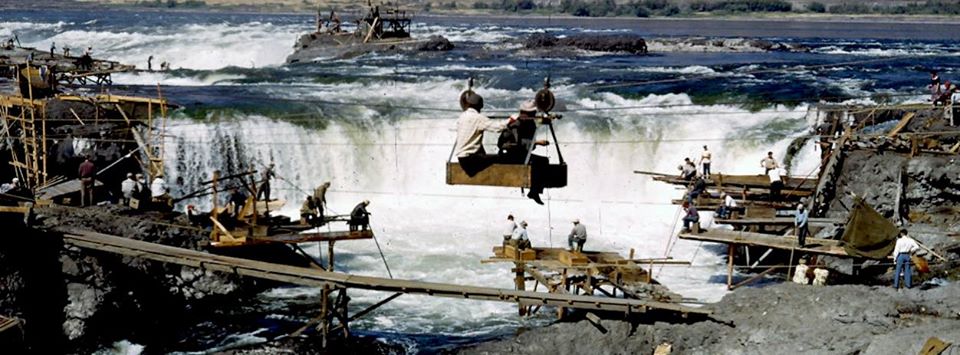

The Columbia Basin Fish Accords were signed by the Umatilla, Warm Springs and Yakama tribes, the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission (CRITFC) and the United States represented by the Bureau of Reclamation, the Army Corps of Engineers and the Bonneville Power Administration. Stemming from nearly a decade of federal courts litigation, the Accords are a series of binding policy and legal agreements that represent a pivotal decision and milestone in the tribes’ decades-long commitment to put fish back in the rivers and restore the watersheds where they live. The three tribal governments and CRITFC agreed not to litigate against hydropower and river operations conditions for a decade. In return, the federal government committed over $600 million to fund highest priority tribal fish recovery and habitat restoration projects.

As a result of the 2008 Accords, efforts directed toward federal court litigation are now dedicated to the restoration of fish runs and improvement of habitat conditions. Though the Nez Perce Tribe chose to not sign the Accords, the tribe continues to implement important fish and habitat projects in the Snake River Basin. The Nez Perce Tribe is also litigating to assure that breaching the Snake River dams is a viable response for Endangered Species Act listings.

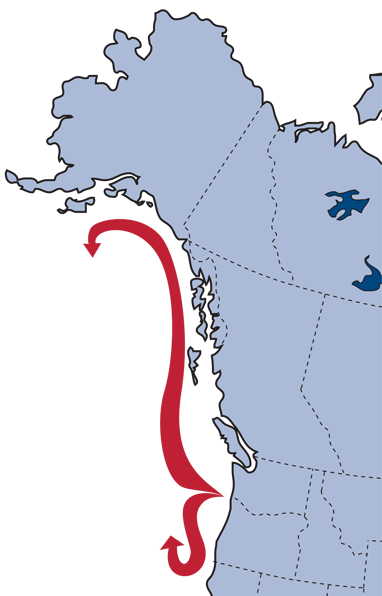

The governments of Canada and the United States signed a new bilateral agreement for the conservation and harvest sharing of Pacific salmon. The product of nearly 18 months of negotiations, the 2008 Pacific Salmon Treaty (amended in 2012) represents a major step forward in science-based conservation and sustainable harvest sharing of the salmon resource between Canada and the United States.

Interception of Pacific salmon bound for rivers of one country in fisheries of the other has been the subject of discussion and frequent conflict between the governments and citizens of Canada and the United States since the early part of the last century. In 1985, after many years of negotiation, the Pacific Salmon Treaty was signed. After an impasse in negotiations resulted in ocean harvest agreements expiring in 1992, the treaty was renewed seven years later in 1999; and most recently in 2008.

In the 1999 agreement, the United States and Canada agreed to regulations that account for annual variations in stock abundance rather than fishery regulations based on negotiated catch ceilings. The new 2008 treaty, in force from 2009 through 2018, will reduce chinook harvest off the west coast of Vancouver Island by 30 percent and Southeast Alaska by 15 percent. The changes send an estimated one million more chinook to Puget Sound and the Columbia River. While chinook are the target species, the agreement also covers coho, chum, pink and sockeye salmon. For nearly 25 years, these consecutive agreements have resulted in more chinook returning to the Columbia River.

The U.S. Pacific Salmon Treaty delegation is made up of representatives from Alaska, Washington/Oregon, 24 treaty tribes, including the four CRITFC member tribes, and the federal government.

Since the mid-1990s, the parties to United States v. Oregon struggled to reach agreement on fisheries and production actions. In many years, litigation occurred and annual or interim agreements were only reached through court-ordered negotiation, settlement orders or rulings of the court. The parties to United States v. Oregon negotiated a successor agreement to the 1988 Columbia River Fish Management Plan from 1997-2008. The 2008-2017 United States v. Oregon Management Agreement was concluded in May 2008, after many years of negotiation. The Agreement, a stipulated court order in United States v. Oregon, will guide management decisions for mainstem Columbia River fisheries and Columbia Basin hatchery programs until 2017.

The 2008 Agreement addresses the fundamental issues the tribes identified at the start of the negotiations. Fishery opportunity is enhanced as compared to previous agreements and treaty harvest will again be protected by federal court order. Hatchery programs crucial to treaty fisheries and tribal fishery programs are part of the agreement. Under the auspices of the federal court, the tribes have the opportunity to engage the states on regulatory issues. The parties formalized commitments to rebuild specific populations to specific levels and agreed to performance measures. In addition the agreement provides a co-management structure and is enforceable in federal court.

The 2008 Agreement also contains significant hatchery fish production commitments. It maintains important hatchery programs, such as the Snake River fall chinook program and various tribal coho programs and provides for increased hatchery supplementation of other important stocks of spring chinook and Group B steelhead. Juvenile release numbers and sites for each interior hatchery program are detailed in Appendix C, 2008-2017 U.S. v. Oregon Management Agreement Production Tables.

The 2008 agreement contains a detailed description of a dispute resolution process. These elements provide the parties with a variety of ways to address technical, legal and policy disputes that may arise over the next 10-year period. Prosecution referral agreements are included in a section on judicial review of disputes.

Finally, the agreement includes a new section on performance measures, commitments and assurances. This section describes the parties’ expectations that the harvest and hatchery production measures will assist upriver stocks to rebuild over time. Performance measures are provided to assist in monitoring progress toward population restoration. If any of the indicator fish populations—those used to measure progress—do not improve as expected, then the Policy Committee could suggest modifying the agreement or make recommendations to other entities regarding additional (non-harvest or hatchery production) actions that could be taken to help rebuild stocks of concern.

The 1990s Endangered Species Act (ESA) listings of Columbia and Snake River salmon brought additional legal and bureaucratic processes into Columbia River fisheries management issues. Most notably, the federal government, through the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS), gained significant regulatory authority over activities that “take”—harm or kill—ESA-listed fish. These activities include ocean and in-river fisheries and hatchery management. If NMFS decides changes are needed in hatchery production programs in the future, the tribes may be forced to again seek judicial relief should the modifications affect the number of fish returning to usual and accustomed fishing areas.

The new hatchery production actions provided for in the agreement will not be implemented without securing new funding. In the current state and federal budget and political climate, acquiring the necessary new funding will be difficult, even with the support of United States v. Oregon parties. The 2008 agreement expires in 2017. For the remaining period of the agreement, key outcomes, which the tribes will monitor closely for achievement, include tribal mainstem fisheries that reach the agreement’s harvest, conservation and allocation commitments, implementation of the agreement’s hatchery production programs and development of regulatory coordination that provides for tribal enforcement.

For more discussion, see institutional recommendations Tribal Hatchery Management and Hatchery Management and technical recommendations Supplementation and Reintroduction.