20th Anniversary of the Spirit of the Salmon Plan

After 20 years, the tribes celebrate their accomplishments and reflect on the importance of using a framework of science and culture.

Science and culture. When the Nez Perce, Umatilla, Warm Springs, and Yakama tribal leaders of the 1990s worked on and guided the development of Wy-Kan-Ush-Mi Wa-Kish-Wit, the Columbia River anadromous fish restoration plan or Spirit of the Salmon Plan, they had a clear vision of what needed to be here for future generations and a strong conviction that the approach to recovery had to involve holistic or gravel-to-gravel management.

Holistic. This approach integrated tributary, mainstem, estuary, and ocean ecosystems —all the habitats where anadromous fish live. It meant examining fish passage, habitat, harvest, and production and recommending substantial changes in current practices and specific actions to recover from historical destructive impacts. The tribes and their staffs developed a series of recommended actions, 13 technical and 11 institutional, combining scientific methodology and social and political processes.

Management complexity. Tribal leaders emphasized that most of the Spirit of the Salmon recommendations extended beyond the means and control of the tribes. They were changes requiring collaboration by a multitude of public and private entities and, depending on the issue, as many as five states, over 25 tribes, and two countries.

Regardless, the tribes engaged the often slow and uncertain public policy processes. Using litigation, control over reservation lands and waters, negotiation, political engagement, and cooperative management, the tribes scored significant successes.

Regional cooperation. Three breakthrough agreements made in 2008 —the Columbia Basin Fish Accords, the Pacific Salmon Treaty, and U.S. v. Oregon Agreements—tackled many of the institutional and technical problems identified in the 1995 Spirit of the Salmon Plan. Together they helped to streamline decision-making and improve coordination among the tribes and federal and state governments.

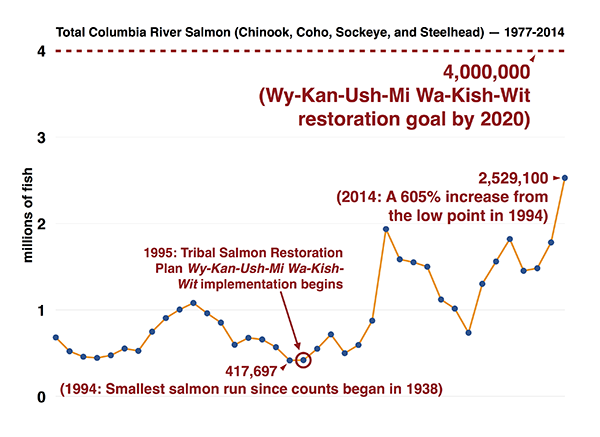

Hundreds of large and small efforts by many entities, tribal and nontribal, have halted the general decline in total upriver salmon and steelhead runs. Two decades ago, some 400,000 upriver salmon and steelhead returned to the Columbia River. Last year, 2.5 million upriver salmon and steelhead returned, setting modern records for fall chinook and sockeye.

Results. With increased salmon runs, tribal members have harvested more salmon, from a more diverse mix of species, and during more times of the year.

Ocean and inriver harvest regulations for Columbia River salmon are now more rational, equitable, and lawful. Today the regulations are based on abundance rather than catch ceilings and support more equitable harvest sharing between Indian and non-Indian fisheries, as called for in tribal treaties.

Alterations to the hydroelectric dams and their operations have benefited migrating juvenile and migrating adult salmon. Spill operations and numerous structural changes at the dams appear to be saving fish from death and injury.

The tribes have returned chinook, sockeye, and coho salmon to rehabilitated streams and lakes where salmon species had been extirpated. The Klickitat, Yakima, Wenatchee, Methow, Okanagan, Umatilla, Walla Walla, Snake, Clearwater, Salmon, Grande Ronde and Imnaha are some of the rivers that have benefitted from tribal habitat restoration and reintroduction work.

Since 2000, the four tribes have used $26.7 million from NOAA Fisheries’ Pacific Coastal Salmon Recovery Fund for watershed restoration. The tribes have invested millions more dollars each year to implemented habitat rehabilitation, habitat research and monitoring, and other projects from funds obligated to address the impacts of federal dams.

The tribes strengthened their individual tribal sovereignty in 2010 by securing law enforcement commissions for officers with the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission (CRITFC) to provide enforcement services on in-lieu and treaty fishing access sites along the Columbia River.

Update. After a dozen years into implementing the Spirit of the Salmon Plan, the tribes directed their staffs to evaluate the progress made, using an adaptive management framework. As a result, the plan was modified and updated in 2014.

Many examples of the tribes’ restoration work are described throughout the pages of Spirit of the Salmon’s 2014 Update.

Both modifications and new technical and institutional recommendations were made during the update. Some changes and additions responded to recent developments in Columbia River salmon management, while others were driven by the challenges of climate change and regional population growth.

The work continues. In recent decades, aquatic and terrestrial invasive species have become more of a threat in the Columbia Basin.Without natural predators and with environmental shifts brought by climate changes, invasive species such as zebra and quagga mussels are likely to affect the river system’s food web and alter habitats. Changes in aquatic habitat and introduction of exotic species have already tipped the predator/prey balance to the point that active management is now required to control predator populations to reduce salmon and lamprey losses.

Responding to the growing evidence that Columbia River fish are exposed to a wide range of dangerous chemicals, the tribes and their CRITFC adapted their strategy for reducing the Columbia’s toxic contamination and improving water quality. The Spirit of the Salmon’s new recommended actions call for the basin’s 15 tribes to develop a unified approach to establishing water quality standards, requiring limits on the use of pesticides and herbicides that make their way to the river, reforming the nation’s Toxic Substances Control Act, and assessing how hydropower projects affect the toxic contamination of fish.

The tribes along with other U.S. entities are reviewing the Columbia River Treaty, an agreement between the United States and Canada made 50 years ago to optimize hydroelectric production and control flooding. The Columbia River Treaty of 1964 does not address the needs of fish or the tribes’ treaty fishing rights. This could change if the two countries decide to alter the terms of the hydropower treaty, in which case the tribes would seek representation on the U.S. negotiating team. Terms of the treaty’s renewal could address restoring ecosystem functions and also fish passage at Chief Joseph and Grand Coulee dams, which would return more salmon to both countries.

Indeed, opportunities to restore fish passage are becoming ever more feasible. Recent developments in juvenile fish passage technology could potentially provide passage opportunities at dams such as Dworshak and the Hells Canyon Complex as well as Chief Joseph and Grand Coulee.

Community Development. In the update, the tribes added new community development recommendations for some of the social and economic infrastructure needs that connect the circle of interdependence between salmon and people.

Working with the U.S. Congress and Army Corps of Engineers, the tribes established new access fishing sites and fishing stations along the river to replace those lost when the hydroelectric dams were built. Tribal housing along the river was also lost during dam construction. The only fishing village to be restored to-date is Celilo, on the Oregon side of the river. Historically, tribal members also had homes on the Washington side.

The four tribes secured funding to build Tribal FishCo, LLC (FishCo), a fish- processing center in White Salmon, Washington. The tribes have yet to capitalize FishCo to bring it up to full operations as a federally compliant food processing facility. The objective is a self-sustaining enterprise, employing and serving tribal members.

Many tribal fishers have now taken food safety and marketing courses, positioning themselves to take advantage of the increased fish runs and better fishing access. As the community development recommendation notes, offering value-added products, such as smoked salmon and filleted fish, and integrating tribal fishers marketing efforts with FishCo are keys to future success.

Future caretakers. More tribal members are making a living in fisheries again — this time not only as fisher men and women, but also as fish technicians, biologists, hatchery managers, and research scientists. While this is true, more positions are available in the fisheries and natural resource fields than there are qualified tribal members to take them. A new generation of Native river caretakers needs to be prepared. Mobilizing resources to help tribal youth acquire appropriate education in science, technology, math, and engineering for tribal youth is an important purpose of the CRITFC Workforce Development Program and the related community development recommendation.

The slow but steady revitalization of the tribes’ fishing culture and economy is testimony to the growing tribal capacity for Columbia River salmon management and implementation of the Spirit of the Salmon Plan.

Informed by the tribes’ vision and with the determination that has allowed tribal members to survive as Indian people since the treaties were penned in 1855, the tribes have rededicated themselves to continue this restoration work so that future generations are blessed with abundant fish spawning in clean, flowing rivers.